Post-release monitoring

Monitoring methods

Direct effects on non-target, beneficial or valued species

In preparation for post-release studies, pre-release opportunities can be taken to enhance robust post-release investigations:

- Population monitoring of a range of potential 'high risk' non-target species

to give a baseline for post-release evaluation. The species list can come from:

- knowledge of host range in country of origin;

- quarantine host range studies in country of proposed new release which indicate potential non-target hosts (van Lenteren et al. 2006);

- literature on known non-target hosts from releases elsewhere;

- knowledge of phylogenetic and ecological affinities of target with fauna in country of proposed release;

- known beneficial species in proposed country of release;

- Surveys of fauna and ecosystem processes in proposed country of release.

- Life table analysis for one or two 'high risk' non-target species so that post release impacts can be quantified. Candidate species can be selected from quarantine data where potential non-target effects have been determined.

- Surveys of potential non-target species in the target host environment.

- Surveys to determine if and where the target pest occurs, outside of the environment within which it is known as a pest, can indicate potential environments in which non-target effects could occur.

- Similarly, surveys outside of the target host environment can be useful for collecting information on the range and distribution of native hosts phylogenetically

- related to the target host.

- For some biological control agents, phylogenetic 'relatedness' to potential nontarget species is less important than habitat, e.g., some leaf-miner parasitoids are able successfully to attack leaf miners from a number of insect orders, but might show specificity to the host plant of the leaf miner complex.

- Information on the mobility of the proposed biological control agent and the target host are useful. Even if the biological control agent is relatively immobile, a host capable of wide dispersal can potentially carry the agent to new habitats.

Then post-release

- Determine which, if any, non-target species (including beneficials and other pest species where appropriate) are attacked in the field by sampling in the target pest habitat and beyond; determine which species and the proportion of non-target populations being attacked.

- Field evaluation of non-target attack should incorporate appropriate spatial, temporal and seasonal scales.

- For predators, gut analysis methods can be used to determine diet breadth e.g., Hoogendorn and Heimpel (2003).

- For herbivorous control agents, long-term monitoring using standardized techniques plus regular observations.

- Development of food web models using stable isotope ratios may be helpful in quantifying how invasions and biological control introductions at various trophic levels affect resource flows in different habitats.

If non-target impact is identified in the field

- Regular sampling programme is useful for determining comparative phenology of the target host and one or more identified non-target species to help predict impact.

- Once a biological control agent is established in a non-target population, life-table analysis is ideal for estimating if impact is feasible. The dynamics here are likely to change over time and space. In weed-control programmes, long-term monitoring of target and non-target populations is essential. Attack alone does not imply that a population level effect will materialize, but declines or increases in plant populations should be recorded.

- Consider developing and testing a predictive model of population impact.

- Match pre-release predictions with post release evaluation. If they match up poorly, ascertaining reasons for this is of value to practitioners and regulators for future biological control proposals.

- If a beneficial species is attacked, it might be necessary to determine how this affects the benefits for which the species is valued.

- Inform the EPA of your findings.

If non-target impact is not identified in the field

- Maintain a low-intensity monitoring programme if possible, e.g., annual sampling at a small number of key sites near such release sites, or at areas of high target impact, and presumably of high biological control agent activity. If a biological control agent is very effective in reducing target populations, there may be a period when the agent is under pressure to locate suitable alternative hosts.

- Competition with or displacement of other natural enemies

- Pre-release information on existing natural enemies (parasitoids, pathogens, predators and herbivores) of the target host, and particularly on identified potential non-target hosts, is useful, so that indirect effects can be ascertained post-release.

- Post-release, non-target hosts can be sampled over time to determine the extent of displacement of natural enemies by the newly released biological control agent and these results compared with pre-release data. This can be integrated with the investigations of direct non-target effects, above.

Longer term impacts

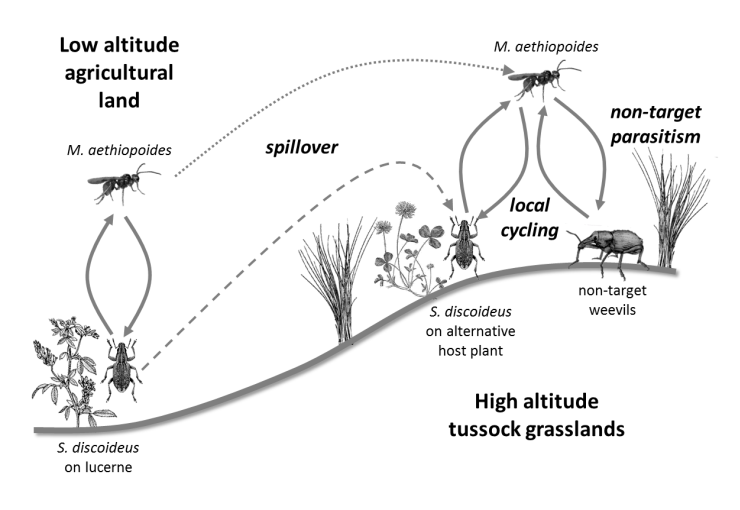

There have been a small number of studies carried out to determine the longer-term impacts of introduced biological control agents but few have considered impacts in natural environments. A study was carried out in New Zealand to look at impacts of the parasitoid Microctonus aethiopoides, a biological control agent for the Lucerne weevil, Sitona discoideus in native grassland Ferguson et al. 2016. The parasitoid also attacks New Zealand native weevil species both in pasture, and to a lesser extent in native grassland. The study sought to determine whether non-target parasitism in native grassland was a result of spill-over parasitism from lucerne areas near native grassland, or whether the parasitoid had become established in native weevil populations in the higher altitude natural grassland ecosystems (see figure).

Schematic illustration of the processes hypothesized to lead to non-target parasitism of New Zealand native weevils by Microctonus aethiopoides in tussock grasslands.

© Copyright AgResearch, used with permission.

References

Ferguson C.M., Kean J.M., Barton D.M. and Barratt B.I.P. (2016). Ecological mechanisms for non-target parasitism by the Moroccan ecotype of Microctonus aethiopoides Loan (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) in native grassland. Biological Control 96: 28-38.

Hoogendorn M. and Heimpel G.E. (2003). PCR-Based gut content analysis of insect predators: A field study. Pp. 91-97 In: Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Biological Control of Arthropods, R. Van Driesche (Ed.) Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, Morgantown, West Virginia.

van Lenteren J.C., Cock M.J.W., Hoffmeister T.S. and Sands D.P.A. (2006). Host specificity in arthropod biological control, methods for testing and interpreting the data. Pp. 38-63. CAB Publishing, Delemont.

Monitoring methods | Indirect effects on other trophic levels and food webs |

|---|